When the guy working out in the gym was introduced to me by a common friend, we discovered that both of us had children in Austin, TX. It was enough for both of us to pursue the conversation and look for more. We found some commonalities and we found some differences. He had worked in high tech, I had been a pastor.

He went on to share that he had grown up in Eastern Europe, that his parents were faithful churchgoers still and that his son was not interested in religion at all but was spiritual. He had found the church to be more focused on dogmatic answers rather than basic questions of life.

He said that questions of what life is for, where happiness is found, what love offers and demands, all of these are spiritual questions, not religious questions. Religion, he maintained, is not about these things but teaches doctrine.

I couldn’t disagree more.

Questions about life’s purpose are fundamentally religious questions. Every religion provides answers to basic questions of human existence, emphasizing certain things and deemphasizing others. While religions are not all the same, neither are they different in every respect.

The author and columnist Ross Douthat has written a new book that speaks to this very question. His book Believe! is precisely about the relevance of religion to “spiritual” questions. His book recognizes that spiritual, not religious, is a growing category of self-description which constitutes an affirmation of basic questions, but a dismissal of religious answers.

Douthat makes the argument that religions all answer questions of meaning and purpose. They speak to fundamental spiritual questions with unique elements of authority and experience. Moreover, while religions are not all the same in teaching or emphasis, there can also be points of agreement. Sometimes they agree, sometimes they differ. Buddhist reincarnation and Christian heaven, for example, both affirm more than a lifespan on earth, but they are also quite different, both in the images and in the foundations of such beliefs.

If religions speak to fundamental questions of human existence, they deserve a hearing, Douthat argues, by everyone, even those who see themselves as “spiritual, not religious.” Spirituality has its own pitfalls. It can easily become a collection of our favorite things, telling us more about our own internal hopes and wishes than about any external reality. It lacks a path to get beyond the self and often lacks real coherence. Its authority ultimately becomes the self.

Douthat then suggests that religions have special authority grounded in the attraction of the founder, the endurance of the tradition, as well as in the attraction of particular elements to us. He invites us into a spiritual quest focused not on comparing and contrasting different religions but on finding some element or elements we find ourselves drawn to in a religious tradition and then pursuing and exploring that connection. It becomes the starting point of a spiritual journey that may take us elsewhere.

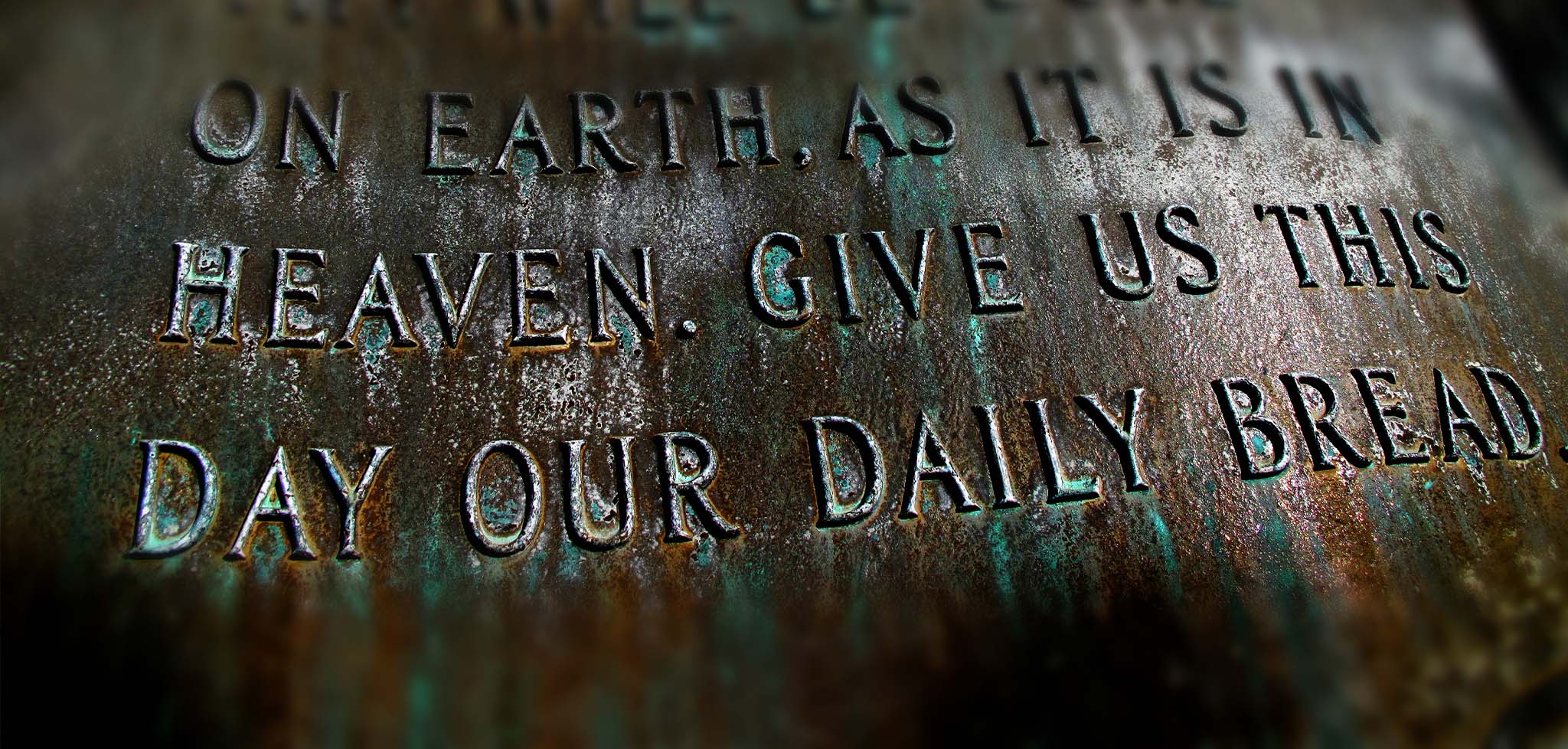

Ironically, the Lord’s Prayer is often overlooked as something more ritualistic than relevant.

It has fallen into the dogma category rather than the spiritual for some, or at least the religious ritual category. But the Lord’s Prayer strikes me as something truly magisterial. It grounds itself on teachings and experiences from Israel’s history. It invites us into a relationship with God, manifests a concrete concern for our life, here and now, and suggests that our life will be most successful when focused on elements which his own life exhibited. The prayer, a response to the request from his disciples, comes from an extraordinary teacher who taught and lived a life of faithfulness and love. It is not something to be passed over, and it speaks profoundly to the life of the spirit.